After 28 hard miles, after cuckoos and curlews and dust and pain and sweat, Gerry Orchard crosses Wheeldale Beck over the stepping stones and sinks to one knee. This is no exhausted collapse; it is the prelude to a song.

“This yah neet, this yah neet,” he sings in a strong Yorkshire voice, “Ivvery neet an’ all. Fire an’ fleet an’ cannle leet, an’ Christ tak up thy saul …”

The Lyke Wake Dirge, which dates back to the 16th century or earlier, was sung over the dead as part of local funeral custom. Since 1955 it has had a curious (after)life of its own, giving a name and a certain gravity to the Lyke Wake Walk, a challenge requiring walkers to cover 40 miles over the North York Moors, between the villages of Osmotherley and Ravenscar, within 24 hours. Singing is optional, though traditionalists with breath to spare may find the dirge soothing, a balm to sore feet and calloused souls.

This, if I manage it, will be my first Lyke Wake Walk; it will be Gerry Orchard’s 220th. He has made more successful crossings than anyone. When Bill Cowley, the North Yorkshire farmer who invented the Lyke Wake Walk, insisted that a “solemn silence should always prevail” upon it, he did not reckon with this man – 62 and whippet-thin – who is as fond of talking as he is of walking, and keen, whenever possible, to combine the two.

“There’s a lot of stories that coffins were carried across the moors in days of old,” he says, “but sadly they’re not true. The real connection with the dirge is that toward the end of the Lyke Wake you feel like death. You look at those tumuli, the ancient burial mounds on the moors, and you think, ‘The guy in there is lucky. He has found peace, whereas I am still suffering.’”

He chuckles. “One day, hopefully, when my time has come, they will bury me under there, and my ghost can heckle walkers as they go by.”

We set off from Osmotherley at a little after 5am, choosing to walk west to east, towards the sea. High spirits, low cloud. It is cold and a little damp.

“That’ll keep the snakes off,” says Gerry: adders are common on the moors. Six geese pass close enough for us to hear the shush of their wings. Bracken pushes, crosier-like, through the hillside. For its first nine miles, the walk passes through a landscape that is semi-agricultural and not unlike parts of the Highlands. One of the challenges and risks of the Lyke Wake is that it is not well waymarked but, here and there, on signposts for the Cleveland Way, some guerrilla hiker has screwed small wooden coffin shapes, painted black.

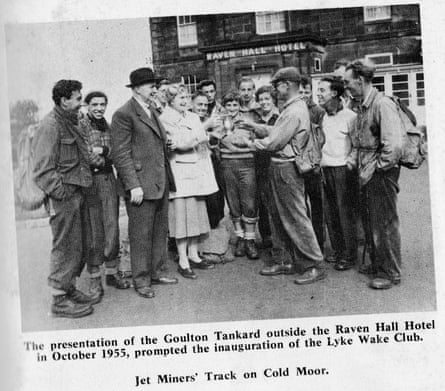

In preparing for the walk, I had spoken with two men who were among the group of 13 who pioneered the first successful crossing, which took place on 1-2 October 1955. Bill Dell, now 78, was a boy scout from Middlesbrough. Malcolm Walker, 81, was a member of York Mountaineering Club (YMC). Both learned about the walk from the Dalesman magazine, where Bill Cowley issued a challenge to anyone who believed they could cover the distance in one day. It was much harder back then, Dell recalled: “There weren’t many paths. You were pushing through heather. We had a break at midnight in a couple of tents up on Blakey Ridge.”

With the hotheadedness of youth, Walker and two others from the YMC decided to set off from this camp before the rest of the party were awake and crossed the finish line, as he recalled with some regret, three hours before everyone else.

“I was in an awful state when I finished but the exhilaration was tremendous. It stretches the body of the average person to its absolute limit. For those of us who couldn’t aspire to climbing Everest, it was the greatest physical challenge we could hope to do.”

The Lyke Wake is an odd mix of the attritional and the intense. You grind out the distance, always mindful you are walking against the clock.

“It’s a war, not a battle,” says Orchard.

It’s also psychological. If the idea of walking 40 miles is overwhelming, try to think of it as several shorter walks. Our plan is to stop, briefly, every time the route crosses a road. Gerry’s partner Julie meets us to replenish water bottles and hand out snacks from the boot of her car.

This saves us carrying too much weight but even a supported walk can be tough. Three-quarters of the way across, I develop large blisters on the sides of each foot and will have to endure the last 10 miles in pain. The famous question posed in Corinthians, “O death, where is thy sting?”, finds a ready answer on the Lyke Wake Walk.

But blisters are nothing. Gerry has seen walkers forced to give up with broken toes, broken wrists and, most commonly, utter exhaustion.

“It can get highly emotional,” he says. “Grown men have been in tears.”

The Lyke Wake can be bleak, the hours slow; time snags and drags in the heather. There is a strong sense of the centuries collapsing into one another. A bronze age barrow, a medieval cross, the sinister pyramid of the RAF Fylingdales early-warning system … All are monuments raised by man, centuries apart – pagan, Christian, secular – yet each with the same twin purpose: hearkening to the universe while leaving some mark upon the Earth.

Gerry will leave his mark, too – if only in the record books. Of the four “centenarians” – those who have completed 100 or more crossings – only two are still alive: Louis Kulcsar, now 80, who arrived in Britain from Hungary in 1956 as a refugee, is the other. Kulcsar, a retired baker, has completed the Lyke Wake 186 times, and has the distinction of having walked it without shoes and socks, an unimaginable feat on unimaginable feet; he has also run it backwards. Gerry has walked the Lyke Wake so many times he could have walked from here to Papua New Guinea instead.

At 8.36pm, in drifting fog, on limping legs, we reach the end: a stone marker just outside Ravenscar. “Stop the clock,” says Gerry, “we’re here.” It has taken 15 hours and 36 minutes. He hands me a patch in the shape of a coffin, and an official New Lyke Wake Club card. “Condolences,” it says, “on your crossing.” Now, if I wish, I can call myself a Dirger.

Personal triumph, however, does not feel like an appropriate emotion at the end of the Lyke Wake. This isn’t a landscape to conquer. It is a memento mori on which one may, briefly, feel never more alive. I’m pleased and relieved to have finished the route but know, even in this moment of excitement, that my footprints have already disappeared into the moors with all the rest.

More information at lykewake.org

Looking for a holiday with a difference? Browse Guardian Holidays to find a range of fantastic trips

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion