So there I was at the beginning of November 2020, sitting in Auckland’s Spark Arena anticipating the Covid-delayed concert by local musical legend Dave Dobbyn, shortly to become Sir Dave Dobbyn and already “world famous in New Zealand”.

I was particularly enjoying the effervescent opening act, Milly Tabak and the Miltones. Fronting the band, Milly hadn’t talked much to the audience other than to acknowledge the band’s delight at sharing the bill with a luminary such as Dobbyn. Now though, she did pause, to offer a lengthy introduction to her next song. It had been inspired, she explained, by her two great-aunts. They were both nurses; one was a spinster, a chain-smoker, and something of a character. The other was a lesbian who had undergone conversion therapy, and had also been a bowler for New Zealand in the 1950s.

By now I was sitting up and paying attention. The advance copies of my book, The Warm Sun on My Face: The Story of Women’s Cricket in New Zealand, were less than two weeks away from arriving in the country and here I was in a concert crowd of several thousand people listening to a singer explain how her great-aunt had played cricket for the national team.

Milly continued. When her great-aunt (the cricketer) died suddenly, she had been matron at Auckland’s Mt Eden Prison where she was held in such regard that the inmates gathered and sang Amazing Grace in tribute, as Grace was her name. Now I was almost certain. Milly was talking about Grace Gooder, who had played one Test for New Zealand against the English tourists of 1948–49. I was sitting open-mouthed in the audience as the band launched into “Hey Sister”.

In 2013 the cricket historian Raf Nicholson had marked International Women’s Day with a piece on her website honouring five pioneering female cricketers. Four of the names spoke for themselves: Molly Hide, Diana Edulji, Myrtle Maclagan and Betty Wilson. The fifth was Grace Gooder.

Gooder had taken six for 42 and two for 31 in her solitary Test. Nicholson highlighted this debut performance and wrote that “little is known about Grace Gooder”. She pointed out that Gooder should have played more Tests but “never got that opportunity”, adding: “I think of her as symbolic of a whole generation of women for whom that is true.” In that darkened arena I wondered whether I might just be about to find out a lot more about Grace Gooder.

The next day I messaged the band to explain my interest in Milly’s great-aunt and suggest that we compare notes. Milly’s reaction mirrored my own shock and surprise. She had been in the car with her partner when she saw the message and exclaimed: “Holy crap! Aunty Grace. Someone at the concert knew who I was talking about!” Later she would write: “Grace passed away in 1983. I never in a billion years thought somebody in the crowd that night would have known of her, let alone picked up on who she was just from my song.”

A couple of weeks later I met Milly at the home of her uncle Simon. There on the table to greet me was Gooder’s New Zealand cap, her Auckland cap and the cap from the North Shore club where she played each weekend. There was also a pair of cricket balls, one of them from the Test in March 1949. But this was just the appetiser. After our mutual introductions Simon opened a case which could only be described as a treasure trove. Press cuttings, photographs, telegrams, articles, mementos – here was the story of Grace Gooder’s life.

Gooder was born in March 1924 and grew up one of three sisters. One was Aunty Bee, the chain-smoking spinster; the other was Milly’s grandmother. Her early years were spent on a farm in Ruawai, a small country town 90 miles north-west of Auckland that is known for dairy farming and kumara, New Zealand’s own sweet potato. The Gooders kept dairy cattle, but the rigours of the Great Depression forced them from their farm and the young family moved to Belmont on Auckland’s North Shore, where they established a market garden on land that today would be worth millions of dollars.

Gooder attended nearby Takapuna Grammar School at the same time as a better-remembered New Zealand cricketer, the great left-hander Bert Sutcliffe, who was five months her senior. Legend has it that Gooder and Sutcliffe were the only students who could throw a cricket ball from the front car park over the school’s main building and into the quadrangle behind.

Gooder had honed her skills skimming stones for hour upon hour at the nearby beaches lining Auckland’s Waitemata Harbour. She also came to recognise many of the ships traversing the Rangitoto Channel to and from Auckland’s port. This became something of a party trick once the second world war broke out, as she could still pick out the regular visitors even in their new garb of wartime grey.

She was always keen on sport, and played hockey and softball as well as cricket. Sport was a constant in the family, with her father a rugby referee and a powerful swimmer who would take to the harbour on a daily basis. Another cousin was a champion cyclist.

After leaving school Gooder continued her cricket for the newly established North Shore Club. In January 1943 she earned a mention in Auckland’s evening newspaper for her fielding prowess, having “held three magnificent catches for Shore” in a match against the Auckland Ladies Hockey Association cricket team. She was in the news again late in 1943 for successful bowling spells and handy late-order batting.

Wartime travel restrictions played havoc with domestic cricket and the Auckland women had not played an inter-provincial match in nearly three years when, on New Year’s Day 1944, the 19-year-old Gooder made her representative debut against Canterbury. She failed to take a wicket in either innings but, coming in at No10 after a top-order collapse, she contributed 15 runs in Auckland’s second turn at the crease. With No9 Dot Simons adding an unbeaten 30, they helped Auckland to reach 103. Gooder’s batting was described in the press as “enterprising”.

Notwithstanding the pair’s efforts with the bat, Canterbury proved victorious, taking the Hallyburton Johnstone Shield back with them to Christchurch. The Shield is the symbol of supremacy in New Zealand women’s cricket, and this match would be the only time Gooder would be on the losing side in a game where the trophy was at stake.

Her teammate Simons had recently moved from Wellington to Auckland and had been instrumental in the formation of the North Shore Club where she and Gooder played. Indeed, she credited the schoolgirl Gooder as helping her start both the new cricket club and the North Shore Hockey Club. Over the following decade Simons, renowned as a pioneering sports journalist and a passionate advocate for women’s cricket, would be a firm supporter of her young clubmate. “Grace was the ideal worker both on and off the field,” she wrote in her obituary of Gooder many years later.

Gooder did not reappear in Auckland colours for another three years. Perhaps this is when she was recovering from a career-threatening accident. She had been thrown from her bicycle as a motorist opened his car door without noticing her approaching. She was seriously hurt. She lost a lot of blood and required a multitude of stitches where the door handle had punctured her back. She was warned that her sporting days could be done with and there was talk of wheelchairs later in life. But the doctors had not reckoned with Gooder’s steely determination or passion for sport.

She was playing again sooner than anyone had expected. It would not be the only time her physical toughness shone bright. In later years she fell down some stairs while holidaying at Houhora then drove the 220 miles back to Auckland without realising that her swollen leg was broken.

It seems that the teenage Gooder had a boyfriend for a time. This may have been a relationship built on family friendships, as Roy hailed originally from Te Kopuru, a neighbouring town to Ruawai where the Gooder sisters had spent their early years. He left New Zealand in April 1942 to serve overseas, becoming a flight sergeant. Roy died in 1944 when the Wellington bomber on which he was radio officer crashed off the Welsh coast, having suffered engine failure during a navigation exercise. He was 23.

At some stage Gooder sought help in addressing her attraction to women. As with her cycling accident, Gooder’s family are unsure of the timing or the details, but it appears she was a patient at Queen Mary Hospital at Hanmer Springs, north-west of Christchurch, where there was a facility dedicated to the treatment of “nervous disorders in women”. Ultimately, an enlightened member of the medical staff suggested to her that perhaps she simply had to accept who she was.

On 24 December 1946 Gooder was back in the Auckland side, with the three-day match played over Christmas Eve, Christmas Day and Boxing Day – how times have changed.

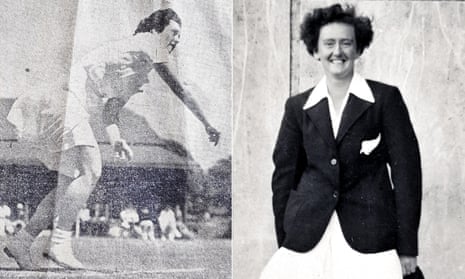

Gooder is generally described as a right-arm medium-pace bowler of considerable stamina. However, Simons expanded on this in 1948, portraying Gooder as a “very heady bowler” who “mixes her deliveries, bowling good-length off-spinners with an occasional fast one on the middle pin, and flights her ball well”. Her family reckoned she might have turned to slower off-breaks when the lengthy spells she bowled early in the innings caused discomfort in her damaged back.

By 1949 Gooder was also playing full-back for the Auckland women’s hockey team and worked in a clerical role for North Shore Transport. Work commitments clashed with the representative calendar and restricted the amount of cricket Gooder was able to play outside of club matches. Hence in 1948 she didn’t turn out for Auckland until the end of February, against Mollie Dive’s Australian touring team. This was the first women’s team to come to New Zealand since the pioneering England side of 1934–35.

When the visitors batted first at Eden Park, Gooder seized her chance, capturing four for 22 – all bowled – to clean out the middle order. But Dive made a century as Australia declared on 222 for seven, and that proved more than enough to ensure an innings victory, depriving Gooder of a second opportunity to show her wares. Simons opined that Gooder had bowled “extremely well”. Auckland’s evening newspaper called her the team’s “top bowler”, adding that “her medium-paced bowling kept the Australians subdued from the outset”.

Shortly after the game Gooder received a telegram from the New Zealand Women’s Cricket Council advising of her selection in the New Zealand XII for the solitary Test of Australia’s tour, to be played at Wellington’s Basin Reserve three weeks later. A follow-up letter suggested that, if she couldn’t find her own accommodation in the capital city, the council would find a family to billet her.

We don’t know where she stayed, but on the eve of the match she was left out of the final XI, missing out on playing in New Zealand’s second-ever women’s Test match. Her omission did not receive universal approval, particularly after the Australians completed victory by an innings and 102 runs. Simons called her absence “very disappointing” given the success she had enjoyed during the summer.

Auckland’s final match of the season was played over Easter, just days after the end of the Test, and Gooder ended with match figures of eight for 65. One article commented that Gooder “showed she was the type of bowler who would have been a great asset in the Test match”.

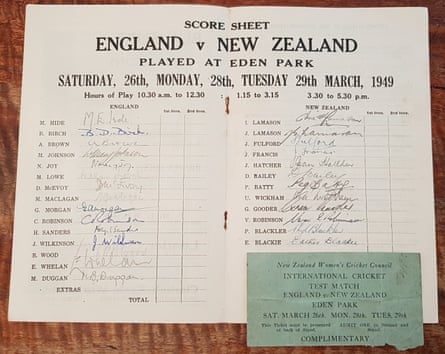

In 1949 England toured late in the summer following their lengthy visit to Australia. Gooder retained her place in the New Zealand XII for the Test at Eden Park in March and was asked to wear the New Zealand blazer she had paid for the previous year.

The Test started in gloomy conditions and showers interrupted play several times after Molly Hide had won the toss and inserted England on a pitch that lacked pace and bounce. Shortly before lunch Gooder struck for the first time. In the afternoon she took five more wickets as England were dismissed for 204.

Gooder had taken six for 42 from 23.2 overs, still the third-best figures by a New Zealand woman in Test cricket. Indeed, until Colin de Grandhomme’s six for 41 against Pakistan at Christchurch in 2016, it was the best debut bowling performance by any New Zealander.

Nancy Joy, a member of the touring party, considered Gooder’s return “thoroughly well deserved” and reward for “bowling with her head and keeping a good length”. Auckland’s morning newspaper described her bowling as “hostile and thoughtful”, while Simons said she had bowled intelligently “as usual”, continually varying her attack.

Unfortunately the home batters couldn’t back up the efforts of the bowlers and the press suggested that the majority of them “were suffering from stagefright”. New Zealand were all out for 61. Gooder enjoyed further success when England batted again, taking two for 31 from her 16 overs to give her the match figures of eight for 73.

In 1949–50, the season after the English visit, the local domestic competition was played on a trial basis as a week-long tournament in Wellington, and Gooder was unable to travel due to work responsibilities. But she was back in the Auckland side the following year, enjoying two five-wicket hauls in one match against Canterbury.

The New Zealand team to tour England in 1954 was to be named after a final trial match at the end of the 1952–53 season, a year before the squad would undertake the long voyage to Southampton. This was to allow the players to raise the necessary £6,000 to fund the adventure ahead.

Gooder was keen to make the tour. She had recently scored a century in club cricket – by no means her first – and played some worthwhile innings for Auckland. Simons called her an “adventurer who swung a meaty bat” but her returns with the ball had been modest by her usual standards and she was not selected for the trial match. When the touring party was announced, her name was missing.

Simons rued the fact that the selectors had restricted their thinking to domestic success in picking the teams for a trial held two months later and felt that Gooder could easily have recaptured her bowling form in the 12 months before the team departed.

That was the end of Gooder’s cricket career. She may have missed out on travelling with the New Zealand team, but she would go to England anyway. Just weeks after the 1954 tourists set sail from Wellington, Gooder left her job of more than ten years and boarded a P&O liner in Auckland. By the time she had reached London she had determined that a career change was in order and she took up nursing studies.

She was very good at it. Among her surviving belongings are numerous certificates from the various courses she completed, normally finishing at or near the top of her class. Gooder’s family have deduced that, because of her success with her studies, she was asked to be one of the pioneers of integrated nursing, where nurses were trained at the same time in both general and psychiatric care. The theory suggested that being able to minister effectively to patients’ psychological needs meant nursing staff could accelerate their physical recovery as well. Gooder became an advocate, and she had articles published in nursing journals espousing the theory and practice.

In the early 1960s Gooder returned to New Zealand and took up a senior nursing position at Oakley Hospital, which at the time was Auckland’s major facility for treating psychiatric disorders. Here she met Margaret, a fellow nurse, and the pair soon became a couple, remaining together for the rest of Gooder’s life. In 1974 she moved to Mt Eden Prison, which at the time housed some of New Zealand’s most notorious criminals. She was appointed head nurse and quickly earned the respect of her charges with her firm, fair, no-nonsense approach.

She was still working there in March 1983 when she suffered a massive stroke and died the day before her 59th birthday. Not only did the inmates gather to sing Amazing Grace in her honour, they also placed their own death notice in Auckland’s newspaper: “For hundreds of men in days of strife, ’twas Grace who helped give purpose to our life. Admired, respected and a dear friend to all the men of Mt Eden.”

It is hard not to wonder how many of them knew that she was a former Test cricketer who had enjoyed one of the most notable debut performances in New Zealand cricket history.

Leap forward to January 2021, and I am back at Eden Park celebrating the launch of my book. Appropriately the event is being held in the Bert Sutcliffe Lounge, named for Grace Gooder’s old schoolmate. The scene is set by New Zealand cricket legend Debbie Hockley, who offers some heart-warming words and a reading from the book. Eventually I ask Milly Tabak to join me at the front of the room to tell the story of how we have come to learn so much about her “little-known” Aunty Grace.

Another of Gooder’s great-nieces, a capable club cricketer herself, had unearthed newsreel footage of the 1949 Test match at Eden Park, and the audience is spellbound as, 72 years on, we watch Grace Gooder and her teammates taking on the might of Molly Hide’s England once again.

Then Milly opens her guitar case and plays a hauntingly beautiful acoustic version of Hey Sister. This time it is not just for Aunty Grace, it is for all the pioneering women cricketers who have gone before and who have given so much to make the game what it is for the female players of today. You could have heard a pin drop.

To Milly go the final words: “I sat there beforehand and looked out on to the fields where Aunty Grace played. It blew me away. Then just being able to play at the book launch – I wanted to cry all night. I’m huge on equality for women, and this experience has been part of my own personal growth. To sing to a room of women who had been trailblazers in the sport – that was truly special to me.”

Originally in issue 34 of the Nightwatchman, Wisden’s cricket quarterly. Get 10% off an annual subscription when you use coupon code GSN12 (12-month subscriptions) or GSNDD (recurring subscriptions) at the checkout. Print and digital formats available.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion